Decision-Making for Unsold Bushels at Harvest – Weighing the Potential Costs and Benefits

This year’s corn crop is on pace to be the largest ever in the U.S. While total U.S. soybean production is down due to fewer planted acres, the yield for farmers has been forecast to increase by an estimated 2.9 bushels/acre to 53.6 bushels per acre. You would hardly be alone if you were facing unsold bushels, inadequate on-farm storage, and the potential for heavily depressed prices at harvest. How can you try to sell the extra bushels you won’t be storing on farm at (hopefully) a better price in later 2025 or 2026? We will look at the pros and cons of four common solutions for delivering grain at harvest while retaining the ability to set the final price well after harvest:

- Commercial storage

- Delayed price (DP) contracts

- Minimum price contracts

- Basis only contracts

What Are the Costs of Waiting?

Keep in mind as you read this article that seasonals and historical price movements are not guaranteed, and may not be likely to occur in any particular year.

In general, we encourage farmers to make cash sales strategically and aggressively earlier in the crop year. Seasonality for both the futures price and basis tends to favor farmers who make sales closer to planting and earlier. In contrast, sales at harvest are generally less lucrative. Seasonality tends to go against farmers close to harvest, especially in years with ample supply. Importantly, monthly post-harvest costs for unsold inventory are not unsubstantial. It is imperative that you calculate the opportunity and out-of-pocket costs you would incur by month as you consider which solutions might make sense and for how long.

Opportunity costs to you:

- What are your scheduled cash flow requirements against cash on hand, including dates and dollars needed? How many months can you meet commitments before you need to cash out unsold bushels?

- What is the opportunity cost to you of NOT selling, money that otherwise could have been used to pay off debt or earn income? As a proxy, calculate lost interest income by multiplying the futures price by the interest rate divided by 12. This equates to the monthly interest cost per bushel owned that should be included as an out-of-pocket cost in assessing your alternatives.

Potential out-of-pocket costs and gains to you:

NOTE: The basis levels in the following examples are used for illustration purposes only and considered accurate as of August 2025. Your local basis may be different.

- What is the typical rebound pattern for basis in your area, historically speaking? This can give you guidance on how long you might need to wait for basis to recover before selling. Here’s why this is important:

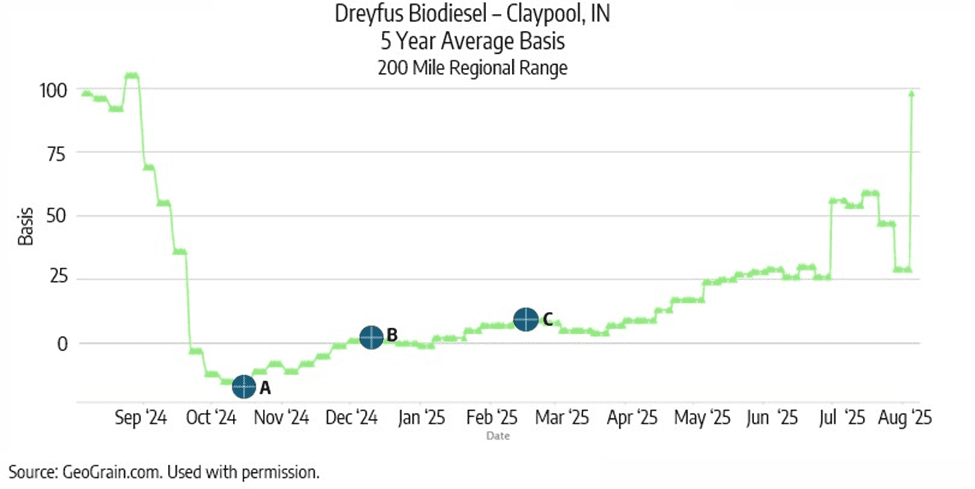

Let’s take a look at Dreyfus Biodiesel in Claypool, Indiana, the largest biodiesel plant in the U.S. The average 5-year basis at harvest is ‑0.17 November (point A in the chart below and 17 cents below the November futures price at the peak of harvest in October), moving up to +0.01 January (point B below and 1 cent over the January futures price) by December and then to +0.07 March in February (at point C below and a 24 cent rebound only 4 months post-harvest). This gives you an idea of how much you historically could have gained in basis by waiting just a few months to sell before considering any potential gains or losses in the corresponding futures prices.

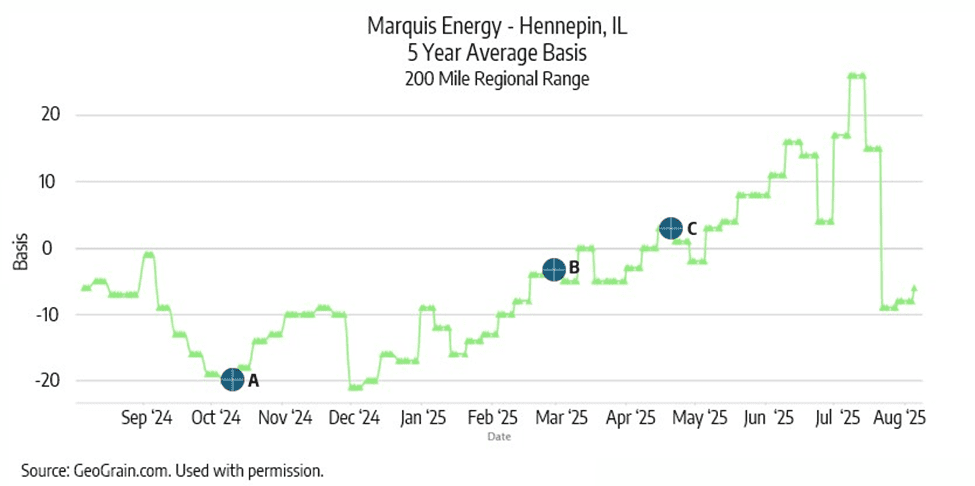

In contrast, let’s take a look at Marquis Energy, the largest corn ethanol plant in the Midwest out of Hennepin, Illinois. A five-year basis average shows the historical average swing from ‑0.20 December at harvest (point A in the chart below) to ‑0.04 March in (late) February (point B below and a 16 cent gain from harvest) to +0.08 July in May (point C below and a 28 cent gain). In this case, the potential payoff, historically speaking, takes longer than with Dreyfus. This means you may need to wait longer to sell, an important consideration as you consider which post-harvest strategy makes sense.

- What is the market carry (the price difference between the nearby and deferred futures contracts), both now and (as you need to continuously watch) later? If the prices on deferred futures contracts are MORE than the nearby contract, this would indicate an oversaturation of supply in the spot market and the potential to make more in the future by waiting to sell.

- What are the monthly commercial storage or delayed price charges you would be charged for stored grain at your elevator or buyer? What are the shrinkage charges, and is there higher moisture shrink for stored grain (corn discounted to 14.5% instead of 15.0% for example)?

Post-Harvest Solutions – Which Might Be Appropriate for You?

Outlining your cash flow requirements and potential monthly storage outlays will help you determine how long you can realistically hold onto the grain, and which, if any, of the following solutions are appropriate for you. The most important consideration is how long it will take for any improvement in prices to outpace the cost of waiting to sell. Here’s a simplified example of what we mean.

Say it costs $0.10/bushel/month to execute a post-harvest solution. What if basis historically takes five months to rebound for a total anticipated improvement between harvest in October and March of $0.27/bushel? That sounds great, except that you spent $0.50/bushel across all your incremental costs on that strategy from October through March. You need futures prices to also increase – by more than 23 cents – to cover your costs. You can continue to wait in hopes of better prices, but your costs will continue to eat away at gains. And don’t forget history doesn’t give you guarantees – basis and/or futures prices could get worse. In the meantime, remember you will need to make a sale at some point, most likely for cash flow. If you need it before prices rebound, your costs may outweigh any return. The more time you have, the better your opportunity to make waiting work in your favor.

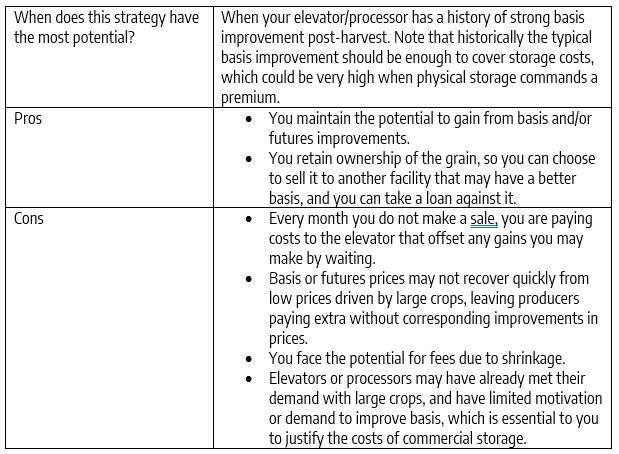

Alternative 1: Commercial storage through an elevator or processor

When you store grain commercially, you pay a monthly fee to your chosen elevator to store the grain. You retain ownership, may obtain a loan with a warehouse receipt, and can price the grain at the elevator when ready to sell or – if you choose – haul it to another facility. Do note that at sale, you may also be subject to additional fees due to moisture shrink.

Alternative 2: Delayed price (DP) contract through an elevator or processor

A delayed price (DP) contract through an elevator or processor (also called a no price established [NPE] contract) is functionally similar to storing grain commercially. You pay a monthly fee to the elevator/processor until you set price. Unlike commercial storage, however, the elevator or processor takes control of the grain. They own it, and you have no ability to haul it away or take a loan against it. Essentially, you pay a fee until you set the price.

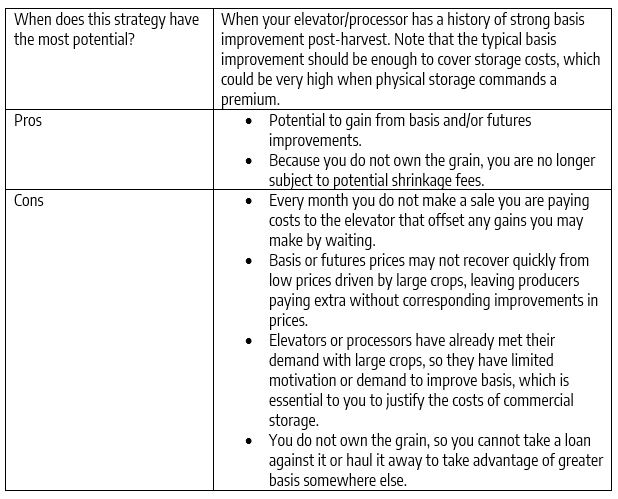

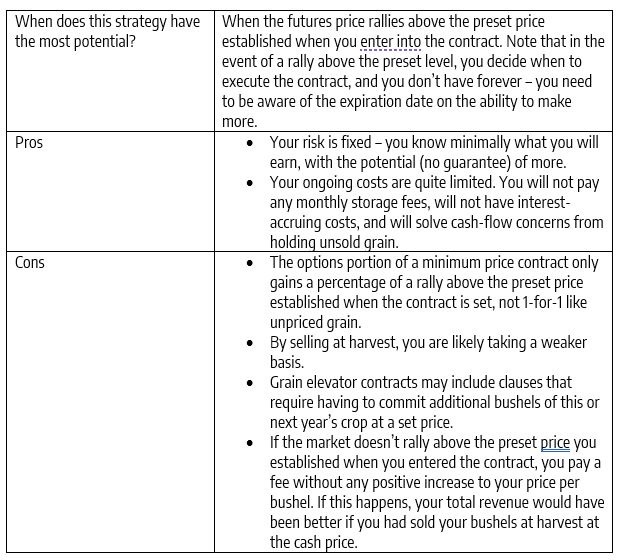

Alternative 3: Minimum price contracts through an elevator or processor (and, in some cases, your broker)

For a fee, many elevators offer a minimum price contract that establishes a minimum price for your grain with the potential to earn more if the market rallies later – specifically, the potential difference between a higher market price and a preset price when you enter the contract. You can also create your own minimum price contract by making a cash sale and buying a call option(s) with your broker.

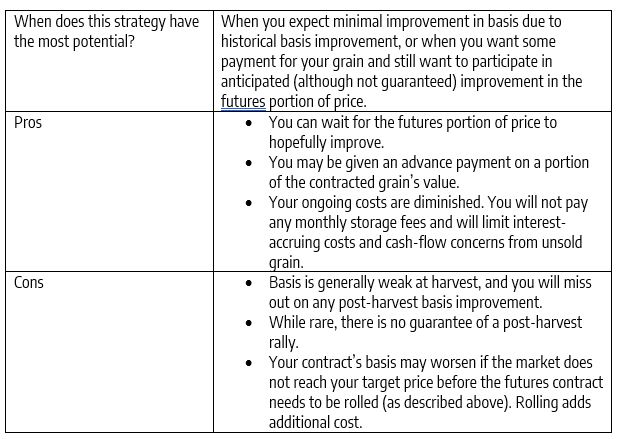

Alternative 4: Basis only contract

With a basis only contract, you set the basis portion of the price for your grain at harvest, and then you establish the futures price later. Note that when you enter into a basis only contract, you need to lock in the futures price before the futures month that the contract was written against expires or the contract is rolled into the next futures month. December corn futures will typically need to be rolled to March (or beyond) by Thanksgiving. November soybean futures will need to be rolled to January futures or beyond by Halloween. Sometimes the spread between these months makes it possible to initially write the contract off the deferred futures, but with big crops on the horizon, that is unlikely.

Make the Best of This Year and Prepare for Next Year

The old adage that the best defense is a good offense is especially true for producers. Though there are no guarantees, making your sales early may reduce or even eliminate your marketing costs, may improve your cash flow, and has the potential to build a better weighted average price. Ultimately, it gives you less to worry about at harvest. Emotionally, it’s hard to make decisions about all your crop when you don’t know how much production you ultimately will have, yet it’s also hard when you have too much.

So talk to us. We can help you evaluate the best decision for your unsold bushels this year, and we can help you make decisions about next year’s crop. We’ve helped farmers work through these pricing decisions for over 40 years, and we’d be honored to help you.

This year, Grain Market Insider is celebrating our 40th year helping farmers. Give us a call at 800.334.9779 to discuss your situation and how we can help you in your marketing decisions.