Marketing Strategies in a Directionless Market

A few years ago, a farmer told me about his successful two-step approach to marketing:

- Listen to what farmers are saying and feeling about the markets.

- When he hears they are getting really excited about where prices are going, he sells because he figures prices are close to the top.

That’s it. That is his plan. And it works for him. He doesn’t care if he gets the best price. He simply wants a good price and figures that is better than the stress of attempting to get (and missing) the top price.

Is this a good approach? In many ways, brilliant. He makes solid, unemotional, and disciplined decisions when the market is in his favor rather than waiting too long. In contrast, many farmers miss opportunities by allowing the emotions of the market to sway them into making the wrong decisions at the wrong time.

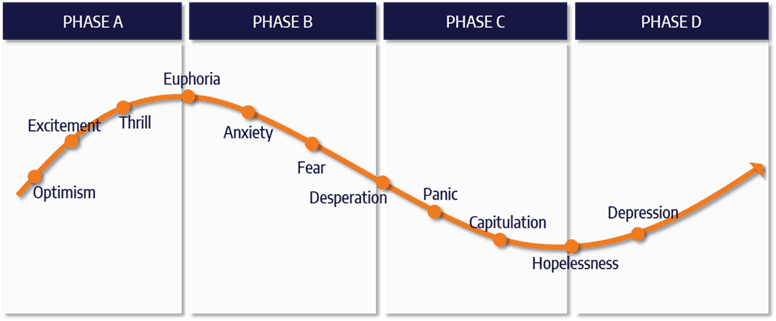

Let’s take a look at the chart below to see how our emotions influence our marketing decisions. When the market is hot (in phase A), market participants get excited and delay making a sale in the hunt for a better price. Many people keep betting the market will rise, until suddenly it stalls and begins to fall (phase B). Some people sell to garner some of the gains, and many people wait for prices to return closer to the high. However, as more and more people start selling and the market becomes more saturated with grain, farmers are suddenly considering sales with prices far from the peak (phase C). At this point, anxiety and fear set in as prices fall and bills come due. It’s at this point where many sales are made in desperation – at the bottom of the market. Right around then, prices start rising again, as the last remnants of grain in the market are being cleared out of the market (phase D) and we return to phase A. In general, your feelings (and, for many, your reactions) reflect where you think we are in the market cycle.

This brings us back to the farmer I was talking about. He operates primarily in phase A as he makes his marketing decisions, allowing himself to take advantage of rising prices without the pain of missing the top of the market. Is his approach one that more of us should aspire to? Before you become an acolyte of this approach, bear in mind that he demonstrates two unusual qualities that allow him to harness the emotions of the market. First, he recognizes that heightened emotions mean the market is getting hotter and hotter; second, he doesn’t get swept up in the emotions. His general mindset may be far more inclined to lock in a good price vs. temperamentally taking a bet on getting the best price. Together, these factors make it easier for him to pull the trigger than the average farmer.

Just as importantly, however, while his approach works for him in a rising market, it really doesn’t help address what to do in a falling or flat market. How do you make a decision when the market is weak for extended time periods and bills are coming due? What if the market really does continue to rise or fall in spite of rather unrealistic market chatter? This calls for a more rigorous approach to work in a number of market environments.

It’s Hard to Tell if Prices Are Headed Up, Down, or Nowhere

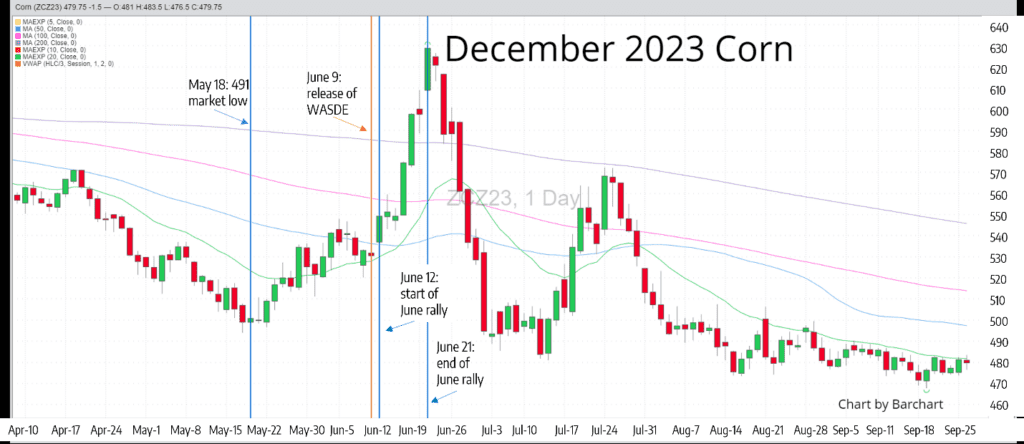

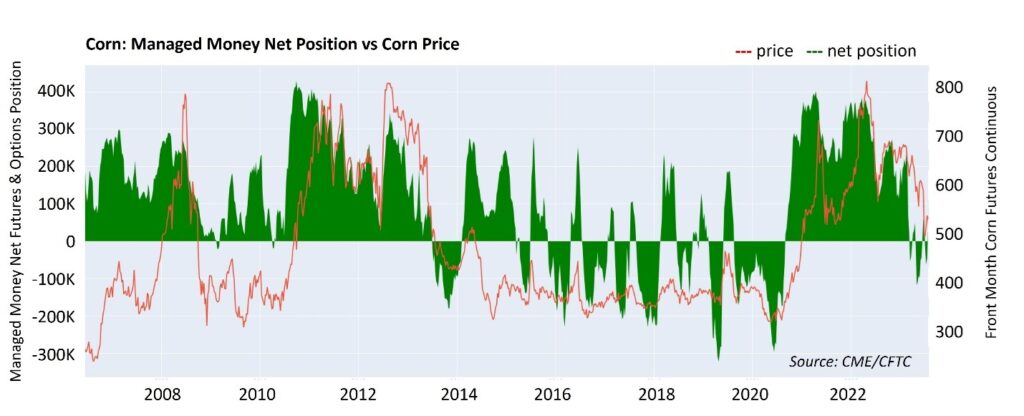

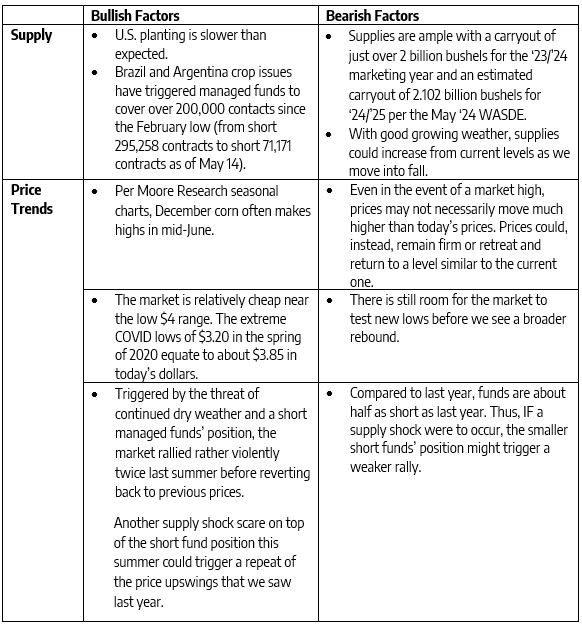

On that note, now is (sadly) a good example of a time when you need to start making decisions in uncertain market conditions. On the bright side, Dec ’24 corn rallied from a low of 446 on February 26 to 496 ¾ on May 15. Is this the reversal of the downward trend you lived through between December of 2023 and the end of February 2024? If you’re on the more pessimistic side, you might feel like this is a blip in an ongoing downward market and you might be inclined to sell, potentially at a market bottom (echoing phase C of the chart above). More optimistically, you might be inclined to sit tight, thinking that the recent rally is the beginning of an upward trend (echoing phase D in the chart above). This, of course, puts you at risk if prices go down.

What is going on that can help us determine where the market may be headed?

Bottom line, prices are soft and have every potential to remain soft. Or not. Under our current conditions, it’s hard to say how prices will move and for how long.

You Need to Plan to Make Sales Regardless of What the Market Is Doing

Selling your crop by the seat of your pants or with the idea of “I only sell when I need the money” can absolutely lead to profitable sales at times. However, it can also have you selling at less advantageous times that could be avoided with some planning. Think about the specific times of the year when you will need extra cash flow for things like machinery payments, rent payments, seed, and chemicals. Also consider when grain needs to be moved to cone down your bins or make room for fall’s harvest:

- Prior to the time you need the cash, plan to make sales as the market presents opportunities.

- When it comes to old crop: identify the drop-dead date that the bins need to be emptied.

- When it comes to new crop: identify how much grain you can store on farm versus what needs to be delivered at harvest. Consider making new crop sales ahead of harvest in lieu of paying commercial storage and selling post-harvest.

- Pay attention to the opportunities seasonality often offers.

- While seasonal tendencies don’t occur 100% of the time, prices tend to be more advantageous during the late spring and into early summer, then again in mid to late winter.

- Note that both old AND new crop sales can be quite advantageous in the late spring and early summer. Soybeans often offer solid opportunities through mid-summer.

- Set up an approach that allows you to take bites out of rising and falling markets.

- As the market moves higher, you price more and more of your grain closer to the top. Similarly, as the market moves lower, you garner value before the price falls too far below the high.

- A stop strategy can help in this approach.

The key is to make plans when you are in control. The last thing you want to do is wait to make a worst-case decision because you don’t have the time or flexibility to make a better decision.

Grain Market Insider can help

For almost 40 years, Grain Market Insider has helped farmers be successful in any market condition. We can help you set up a plan that prepares you for whatever the market does rather than on what you hope it will do.