Are You Missing Out on Higher Prices?

The other day I heard a group of GenZers throwing around the term FOMO – fear of missing out. It’s a newish term for an overwhelming apprehension that friends and acquaintances are having rewarding experiences that you aren’t part of, triggered by doomscrolling on social media.

This might sound a little familiar to a farmer. Many suffer from their own form of FOMO year after year. It goes something like this:

- Read conflicting market news and reports without consistently clear direction (because, really, you can’t predict the market with any certainty).

- Sit tight on making sales because you worry that, unlike fellow farmers, you might miss out on higher prices.

- End up missing out on better prices for the most part and instead selling at a lower price on average.

In other words, FOMO for farmers can actually cause their fear to become their reality, especially if you look at average revenue over time.

Can You Really Reduce FOMO and Increase Your Average Price Potential?

It’s very possible to increase your revenue potential over time: stop chasing the highest price and instead make sales on a consistent basis when, historically, the odds are in your favor. Yes, yes, yes, it sounds boring and even risky (after all, you’re giving up on the idea of getting the BEST price), yet the math shows that this lower stress approach may offer you a potentially better average price over time. To illustrate what we’re talking about, let’s do the math on two hypothetical farmers, FOMO Freddy and Steady Eddie.

FOMO Freddy’s marketing strategy

FOMO Freddy is very focused on getting the best price. He likes to make sure he allows for sales throughout the year, because he knows that high prices can happen at any time based on different events.

- Bear in mind, he does need to make sure he generates enough revenue with sales to keep operating the farm, and as a result makes sales when necessary. In other words, in order to maintain the potential for the highest sale, he also (from time to time) might need to make sales at seasonally lower prices to generate needed revenue.

- This approach has the potential for incredible marketing years if the timing is right. However, bear in mind that this approach is a bit like gambling. How many years in a row can you beat the House? (Or in this case, the average return of the market.)

Steady Eddie’s marketing strategy

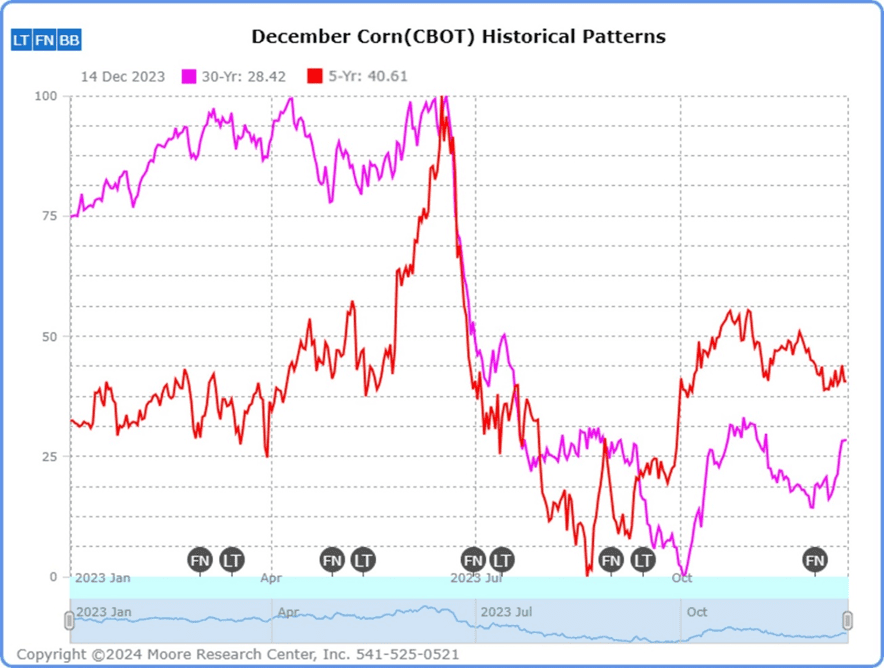

Steady Eddie, on the other hand, sticks to his plan religiously. He knows by the historical price charts and experience that prices tend to be historically higher between March 1 and June 30 (see the historical pattern chart below). As a result, every year prior to harvest, he incrementally sells 50% of his crop between March 1 and June 30. He sells the remaining 50% incrementally the next year, again between March 1 and June 30. With this approach, he is never boxed into selling his crop near the harvest low.

- Bridging sales between years can make a big difference on your average price, even in years with a large projected yield. To be sure, anticipated supply rises and prices fall accordingly heading into what might be an expectedly large harvest, and early sales may be less advantageous in the end when supplies shrink and prices rise. However, they can be averaged with the better prices attained with later sales the following year.

- Steady Eddie avoids leftover inventory and not enough new crop sold heading into harvest and the post-harvest part of the marketing year.

- In return for the consistency and reliability of this approach, he forgoes the potential to make sales during any high price period outside of the window of his plan.

Looking at the Math

In order to illustrate the potential of Steady Eddie vs. FOMO Freddy over time, we’re going to look at how their strategies play out, on average. We’ll do that by pricing out their returns based on daily averages from 1988 through 2003.

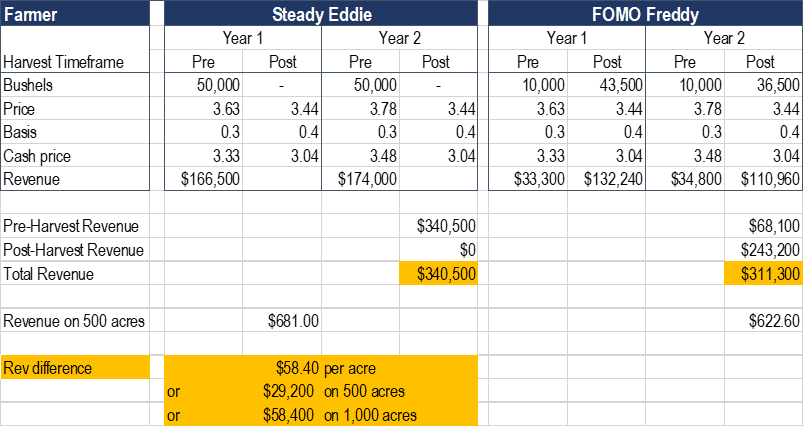

Scenario 1: FOMO Freddie Really Holds Back on the Hunt for Higher Prices

- Both Steady Eddy and FOMO Freddy have a crop size of 100,000 bushels on 500 acres (or 200 bu/acre)

- Steady Eddy sticks to his plan and sells 50% incrementally between March 1 and June 30 pre-harvest and then again between March 1 and June 30 pre-harvest the following year.

- FOMO Freddy only sells 10% of his crop between March 1 and June 30 in the hopes of better prices later in the year. To generate a revenue comparable to Steady Eddie by year end, he sells slightly more than 40% of his crop between September 1 and November 30. He follows the same approach the following year with less than half his crop.

Pricing assumptions:

- The Mar-June average price for pre-harvest sales made in spring is the average daily price for that time period for the years 1988-2023 using the December futures contract.

- The Sep-Nov average price for the harvest sales for old crop and new crop is the average daily price for that time period for the years 1988-2023 using the December futures contract.

- The Mar-June average price for spring to sell the second half of the previous year’s crop is the average daily price for that time period for the years 1988-2023 using the July futures contract.

- Basis levels are typically weaker at harvest. In this case, we assume a 10 cent weaker basis for the bushels sold just before or during harvest than the bushels sold between March 1 and June 30. This isn’t always the case. In rare cases, such as this year in some areas, basis levels can be 20-30 cents lower at harvest than other times of the year.

- We are not accounting for the costs of commercial storage, DP charges, or interest.

Under this scenario, Steady Eddie could potentially make $58.40 MORE per acre than FOMO Freddie. That equates to $29,200 more per year on 500 acres or $58,400 on 1,000, or $730,000 and $1.46 million, respectively, over 25 years!

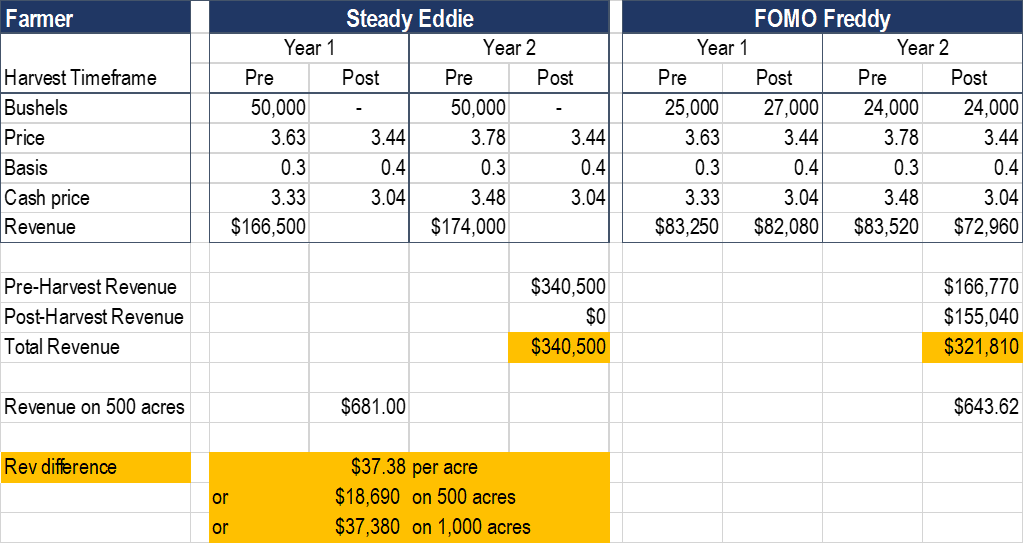

Scenario 2 (a.k.a., the Let’s-Be-More-Realistic Scenario)

There may be some among you rolling your eyes a little at the scenario above. After all, who would really behave like FOMO Freddie year after year? The advantage to his approach is the flexibility to adjust when sales are made year after year to account for opportunity. In this scenario, FOMO Freddy will sell grain more evenly at the run-up of prices in spring and then close to harvest. Let’s take a look at what happens:

- Both Steady Eddy and FOMO Freddy again have a crop size of 100,000 bushels on 500 acres (or 200 bu/acre)

- As in the first scenario, Steady Eddy sticks to his plan and sells 50% incrementally between March 1 and June 30 pre-harvest and then again between March 1 and June 30 pre-harvest the following year.

- FOMO Freddy sells 25% of his crop between March 1 and June 30 (up from 10% in the previous scenario) in the hopes of better prices later in the year. To generate a revenue comparable to Steady Eddie by year end, he sells 27,000 bushels of his crop (2,000 more than in the spring) between September 1 and November 30. The following year he sells half his remaining crop (24,000 bushels) between March 1 and June 30 and then the rest of it between September 1 and November 30.

Pricing assumptions: same as Scenario 1

Under this scenario, Steady Eddie could potentially make $37.38 more per acre than FOMO Freddie. That equates to $18,690 more per year on 500 acres or $37,380 on 1,000, or $467,250 and $934,500, respectively, over 25 years. Again, saving sales for historically lower prices in the hopes of higher prices sets you up for lower average prices.

Now, realistically, these are hypothetical numbers. Consider the assumptions that got us to this hypothetical revenue differential and remember that it’s MUCH easier to replicate a more accurate number for a consistent approach than one that changes year over year. And then think about how often you beat the averages with the approach you generally take, especially if your approach is more like FOMO Freddy’s. Realistically, for many, the consistent approach is more reliable and offers greater potential return even if – especially if – you marketing isn’t focused on hitting the high.

The Bottom Line

At the end of the day, it’s all about the bottom line. However, it’s more than that.

- It’s about your peace of mind and knowing that, over the long term, your best bet to get the best average price lies in consistently pricing your crop during timeframes that offer the best chances of offering the best prices.

- It’s about more consistent income, especially in years of low prices, which allows you to expand your operation every year, not only when prices are abnormally high.

- It’s about the potential to lower overall interest costs. As money comes in on a more regular basis, it can help reduce any interest paid with smaller earlier payments versus later and larger payments.

- Consistent marketing helps with cash flow … always having grain sold prevents having cash flow issues and again, the need to sell at inopportune times.

- Finally, consistent marketing helps you avoid expensive commercial storage or delayed pricing fees by having enough sold ahead of harvest.

At Grain Market Insider, we’re close to celebrating 40 years of helping farmers make smart, consistent decisions about their marketing. Talk to us about how we can help you eliminate your FOMO.

Give us a call at 800.334.9779 to learn more.